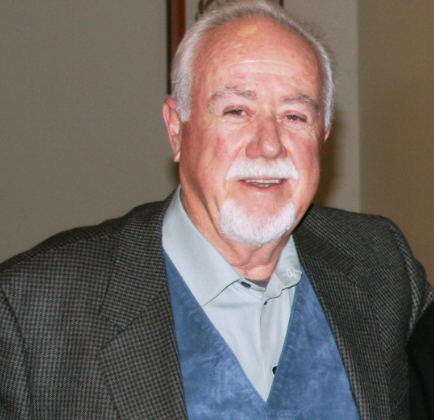

Dr. Gerald Zinfon, Professor of Poetry, Plymouth State University

One day my boss, a prominent attorney in Sarasota, stopped our conversation about scheduling clients and said, “You know, Mary Catherine, you really should be in college.”

Four months after this man took the time out of his jam-packed day to advise me as he might have one of his own daughters, I was enrolled at a state college in New England. My boss lost a secretary and I, with no exaggeration, gained a life.

For him, it was a passing moment of advice to his young secretary; for me — since my own dad had left the scene years before — it was the kick in the butt I needed from a father figure I’d never had.

I’ve never forgotten him — the man whose advice set about the chain of events that culminated five years later with me staring up at the Eiffel Tower — less than a week after graduating, summa cum laude no less, and the first woman in my family to even go to college. And while he was the first man to give me a fatherly push forward, he wasn’t the last.

Another boss — a man for whom I worked as a part-time secretary in between classes and during semester breaks — advanced my paycheck countless times to help me meet tuition deadlines and buy books for classes.

A journalism professor was the first to tell me my work was “publishable” and helped me land a newspaper internship — launching a life-long love affair with the printed word.

Another professor, Dr. Gerald Zinfon of Plymouth State University, after I’d won a poetry fellowship to study at Bucknell University, worked behind the scenes to arrange financial assistance so that my bills would be paid while I left my part-time job for four months. A third professor, knowing my dream of working in Paris, went out of his way during my final semester to help me take the language fluency tests required by the French government to grant my permit du travail — a work permit that would allow me to live and work in the city of my dreams after graduation.

These men taught me that the measure of a father isn’t found in DNA. It’s found in the way a man shows up and sticks around and, yes, even fades into the background when his work is done, giving just enough of himself, his time and his advice to empower, but not overpower, a younger person’s own natural instincts to seek adventure, learn, grow and establish a career and identity.

As much as our mothers can and want to do for us, fathers uniquely fill special needs for both boys and girls. Luckily, they don’t have to be biologically connected to a young person to have a positive influence — they can be trusted family friends, neighbors, clergy, teachers, coaches and even bosses.

My stand-in fathers were men of varying ages and professions, with and without children, who showed up at moments when I needed them most during my 20s, waking me up to the fact that even though my biological father had chosen to drop out of my life, I didn’t have to drop out of it too.

When I was younger, I used to say I never had a “real” Dad. Now I know those men — the ones who, whether with a few words or with years of supportive actions, took the time to embolden me to dream bigger, to see more, do more and be more than I ever thought possible — they were my fathers.

Because any man who helps a child find the courage and the means to pursue his or her dreams — that’s a real Dad by any measure of a man.